Breast cancer is now the most commonly

diagnosed cancer in the world.

Cancer is a group of diseases involving the uncontrolled growth and spread of abnormal cells that can destroy healthy tissue in the body. Typically, cells die when they get too old or damaged, and DNA signals for new cell growth. Cancer occurs when a genetic change occurs and disrupts this process. Usually, these genetic changes develop over time and are not inherited from parents.

When a cell keeps dividing and producing more cells without proper regulation, a mass of unwanted cellular tissue, like a tumor, can form. If the cells in that tumor don’t invade nearby tissues, they are considered benign or non-cancerous. If the abnormal cells can spread to surrounding tissues and other parts of the body, the tumor is malignant or harmful.

In the United States, one out of every eight women will be diagnosed with breast cancer during her lifetime [2]. Breast cancer can develop in the milk-producing glands known as lobes or connective tissue in the chest, but primarily occurs in the milk ducts of the breasts. Everyone has some glandular tissue in their chest, which is why we all carry some level of breast cancer risk.

Breast cancer is not a single disease but a collection of cancers that are categorized by the tumor characteristics. Growth rates depend on many factors including the type of cancer, age at diagnosis, immune response, and the presence of other diseases. These differences in growth rates mean that some breast cancers could take as little as two years to reach a size that’s big enough to feel, while others that grow more slowly could take over ten years to reach that same size [3,4].

What Fuels Breast Cancer Growth?

Breast cancer growth is often fueled by hormones in the body, especially estrogen and progesterone. These cancers are considered hormone receptor-positive cancers. Approximately 80 percent of all female breast cancers are influenced by estrogen while two-thirds of cases are fueled by progesterone [5]. Even though men have reduced amounts of these hormones, they can develop breast cancer (although male breast cancer is far less common than female breast cancer). Nine out of ten male breast cancers are hormone receptor-positive [5].

Some cells produce too much of a protein called human epidermal growth factor 2 (HER2) which can promote cancer growth. This overabundance is found in 20-25% of breast cancer cases [5]. A less common yet more aggressive form of breast cancer, referred to as triple-negative breast cancer, is not fueled by any of these factors.

Research has identified several hormonal, chemical and genetic factors that are known to influence our breast cancer risk. Some risk factors, such as being born female and aging, are beyond our control. However, there are several lifestyle-related risk factors that can be modified to lower breast cancer risk.

How Is Breast Cancer Detected?

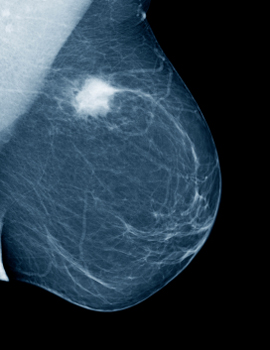

Although the most common sign of breast cancer is a lump found in the chest or underarm, there are other visual signs that can alert us as well. Breast cancer found in its earliest stages is highly treatable. We suggest everyone practice early detection, and women should follow a three-pronged approach for finding breast cancer as early as possible. For people of average risk, we recommend:

- Everyone performs the monthly breast self-exam by age 18

- Women start yearly clinical exams by age 19 but no later than age 25

- Women begin yearly mammograms by age 40

How is Breast Cancer Diagnosed?

Screening methods are a great way to detect suspicious lumps, but they do not determine whether a mass is benign or malignant. In fact, about 80% of breast lumps are harmless [6]. The only definitive way to diagnose breast cancer is through a biopsy, which is the partial or complete removal of the suspicious lesion for analysis by a pathologist. Fine needle biopsy is an effective, non-surgical means that uses either ultrasound or mammography to locate the suspicious lesion, and then remove several small samples for evaluation. Under certain circumstances, a surgical biopsy can remove tissue from a suspected mass for diagnostic testing.

How is Breast Cancer Treated?

Treatment options are evolving on a continuous basis. More so than ever before, breast cancer treatment has become highly personalized, based on the genetic makeup of the individual as well as the tumor. Not all interventions are available to all breast cancer patients. In recent years, there has been a focus on offering treatment before cancer surgery or other primary cancer treatment. This is done to monitor the effectiveness of the treatment and either to avoid surgery or improve surgical outcomes

Breast cancer treatments fall into two categories:

Localized treatment: only treats the tumor or very specific area, without affecting the rest of the body. Local interventions, like surgery and radiation therapy, may be the sole mode of treatment for early stage cancers, or a combination of localized and systemic treatments may be used for more advanced cancers.

Systemic treatment: can reach cancer cells anywhere in the body, using drugs which can be given orally or directly into the bloodstream. Tumors are tested for certain biomarkers that help the doctor make more informed decisions about the course of treatment. Systemic options include:

- Hormone therapy

- Chemotherapy

- Immunotherapy

- Targeted Drug Therapy

If cancer is found early, more treatment options are available, and the regimen may be more tolerable. Finding breast cancer in its earlier stages greatly increases survival rates, which emphasizes the need of practicing every available method of early detection.

Sources

- Sung, H, Ferlay, J, Siegel, RL, Laversanne, M, Soerjomataram, I, Jemal, A, Bray, F. Global Cancer Statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN Estimates of Incidence and Mortality Worldwide for 36 Cancers in 185 Countries. CA Cancer J Clin. 2020.

- American Cancer Society. Breast Cancer Facts & Figures 2019-2020. Atlanta: American Cancer Society, Inc. 2019.

- “Natural History and Prognostic Markers.” Holland-Frei Cancer Medicine. 6th edition. 2003.

- Nakashima, K., Uematsu, T., Takahashi, K. et al. Does breast cancer growth rate really depend on tumor subtype? Measurement of tumor doubling time using serial ultrasonography between diagnosis and surgery. Breast Cancer 26, 206–214 (2019).

- Howlader N, Noone AM, Krapcho M, Miller D, Brest A, Yu M, Ruhl J, Tatalovich Z, Mariotto A, Lewis DR, Chen HS, Feuer EJ, Cronin KA (eds). SEER Cancer Statistics Review, 1975-2017, National Cancer Institute. Bethesda, MD, https://seer.cancer.gov/csr/1975_2017/, based on November 2019 SEER data submission, posted to the SEER web site, April 2020

- Perry MC. Breast Lump. In: Walker HK, Hall WD, Hurst JW, editors. Clinical Methods: The History, Physical, and Laboratory Examinations. 3rd edition. Boston: Butterworths; 1990. Chapter 170.